Ah, Belle Epoque Paris: a lost world of artists, writers, dancers, philosophers and …. potheads? Today, we’re getting acquainted with the long forgotten Club des Hashischins, “Club of the Hashish-Eaters”, a 19th century gang of Parisians dedicated to drug-induced experiences, whose members included a gaggle of the most prolific intellectual names, including Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, Charles Baudelaire, and Honoré de Balzac to mention a few. Snacks ready? Let’s light this one up…

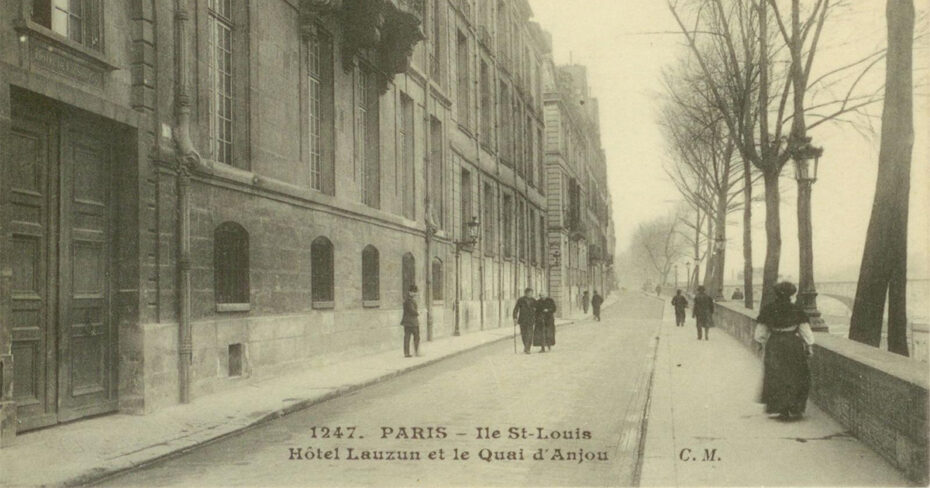

Hôtel de Lauzun

Our collective of creative Parisian ‘hash-heads’ met regularly in the heart of Paris between 1844 and 1849 on Ile St-Louis at the gothic Hôtel de Lauzun, the rented townhouse of 19th century painter and musician Fernand Boissard. Charles Baudelaire, who at the time was busy translating the works of Edgar Allan Poe, writer Victor Hugo (best known for his novels Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre Dame), novelists Alexandre Dumas (The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo) and painter Eugéne Delacroix, among other famous heavyweights, regularly dipped in and out of the ‘Club of the Hashish-Eaters’ suitably dressed in bohemian attire. The glue that cemented this social club together was of course the drug hashish, a highly potent form of cannabis made by compressing and processing the flowering buds of the female cannabis plant. The drug has been consumed for centuries – the exact date of its first appearance isn’t clear but northern India and Nepal have a history of thousands of years of producing it.

It only made landfall in Europe in the 19th century after French troops were introduced to it in Egypt during the Napoleonic campaigns. The timing for its introduction to Europe and particularly Paris couldn’t have been more perfect: with the extremes of the revolution over, the 1840s saw Paris momentarily calm under the restored but laissez-faire ‘Citizen King’ Louis Philippe. A friend of Britain, yet a supporter of the revolution, he avoided the pomp of the previous royalty, his rise from poverty to kingship so vividly described by Victor Hugo in his novel Les Misérables. Europe was on the march, eyes were opening onto the new industrial and trading world and everything oriental was in vogue. Bling, bawdy and benumbed, all sensory experiences were to be assimilated – from the overly colourful images of the French Romantic painters to the exotic and intoxication potions from the Far East. To boot, one of the first great “drug writers”, Thomas De Quincey, had published Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (translated in 1828 by Alfred de Musset) to both immense fascination and outrage of 19th century audiences, and in the process attracted intellectual disciples like social critic and aesthetic French commentator Charles Baudelaire – who then proceeded to plagiarise much of the work for his own drug memoir, Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil).

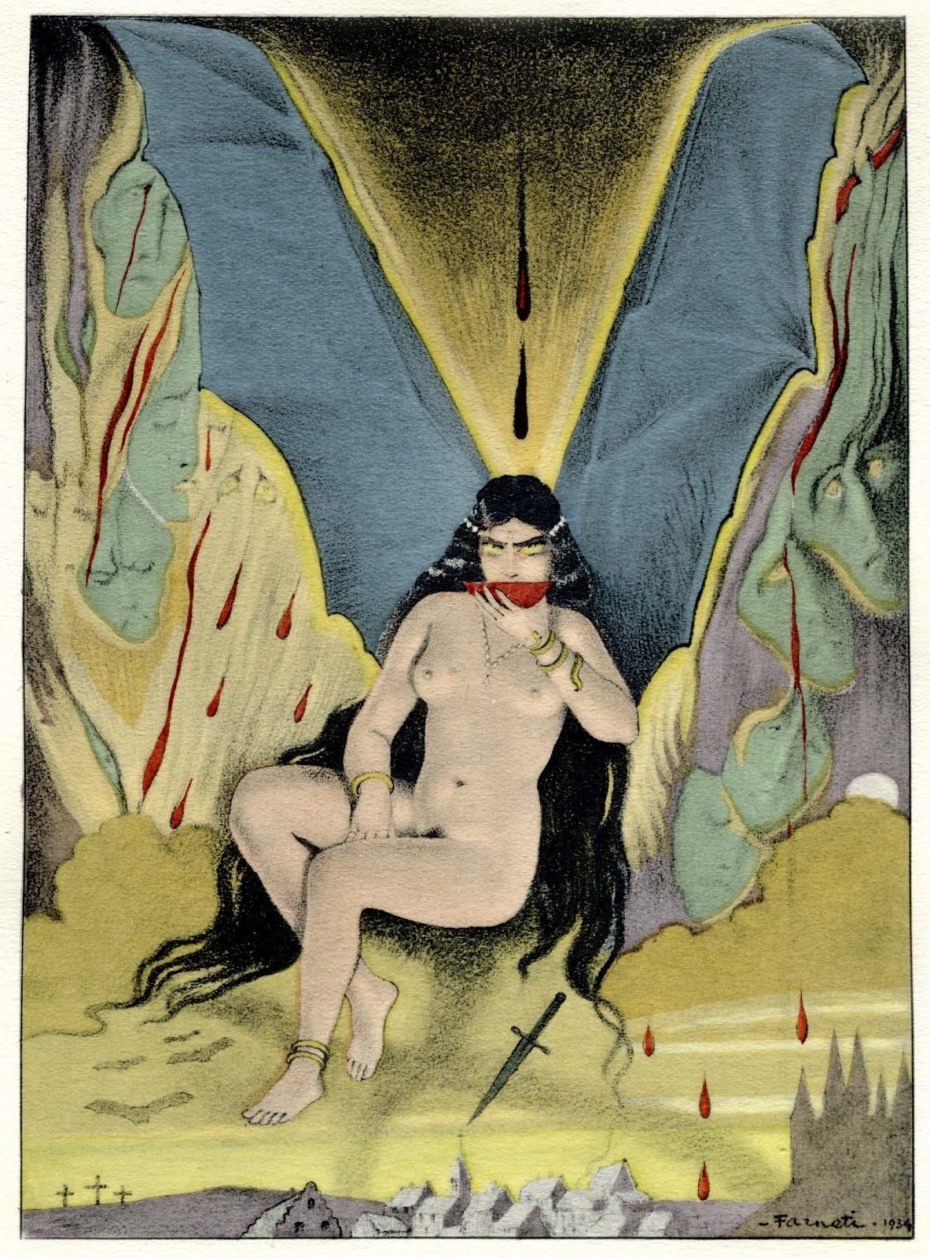

Carlo Farneti’s illustrations for “Les Fleurs du Mal” by Charles Baudelaire, 1935

The Hashish Club at Hôtel de Lauzun was the brainchild of psychiatrist Dr Jacques-Joseph Moreau. Moreau had launched his psychiatric career by escorting patients with mental health issues on lengthy therapeutic journeys to exotic places, and on one such trip to Egypt and Turkey, he had encountered hashish. He theorised that the symptoms of psychoactive drugs like hashish were very similar to those of mental illnesses and wondered if the drug could in fact be used to help cure them. He was fascinated with hallucinations (often a precursor to mental illness) and wanted to experience these false sensory perceptions and their effects first-hand … without necessarily experiencing a mental breakdown. Back in Paris, he set about assembling a set of willing volunteers who he could observe in a drug-induced state in order to test his theories. And so it wasn’t long until an enthusiastic, glittery-eyed, red-cheeked Moreau started dispensing hashish among the intelligentsia he encountered at various Parisian salons. (Jacques-Joseph Moreau eventually went on to publish a ground-breaking work about the effect of a drug on the central nervous system, Du Hachisch et de l’aliénation mentale, in 1845.)

Hotel de Lauzun

But let’s pause for a moment and picture these intense monthly get-togethers and their bohemian lair; members would congregate in an ancient house’s dimly-lit room, antiquated furniture was draped with threadbare and faded old-world tapestries, the entrance door cloaked behind a mysterious velvet hanging, archaic undulating wall panelling with peeling guilt work, faded erotic romantic paintings; the room capped with a crumbling dusty corniced dome. The gathering was a motley crew of wild and woolly-looking men, bedecked in outlandish costume, whose appearance was even more weird and witchy in the flickering dim candlelight.

Théophile Gautier, after his first visit described this ‘chill’ room in an article titled ‘Le Club des Hashischins’ published in Revue des Deux Mondes (1846):

“One December evening, obeying a mysterious summons, drafted in enigmatic terms understood by affiliates but unintelligible for others, I arrived in a distant quarter, a sort of oasis of solitude in the middle of Paris … that seemed to defend against the encroachments of civilization. It was in an old house … that the bizarre club of which I was a member … held its monthly sittings where I was to attend for the first time. Although it was scarcely six o’clock, the night was dark.”

The host, Moreau, with his pulsating, ‘protruding veins’ and ‘dilated nostrils’, would ceremoniously serve the walnut-size portions of dawamesc (dessert) to his willing guinea pigs in Oriental porcelain serving dishes: the offering a concoction of goo-ey jam-like green paste made of hashish, sugar or honey, butter, orange juice, nutmeg, cloves, cinnamon, pistachio – and often the aphrodisiac Spanish Fly would be the pièce de résistance. Although the ingredients resemble a spicy Christmas cookie mix – albeit with the promise of a psychedelic trip and heightened libido, participants reportedly did experience some mind-blowing hallucinations, exaggerated senses and rapacious appetite. Moreau noted ecstatically, that,

“It is … really happiness which is produced by the hashish; and by this I imply an enjoyment entirely moral, and by no means sensual, as we might be induced to suppose. The hashish eater is happy, not like the gourmand or the famished man when satisfying his appetite, but like him who hears tidings which fill him with joy, like the miser counting his treasures, the gambler who is successful at play, or the ambitious man who is intoxicated with success.”

The dawamesc and Turkish coffee were served before the main course, the idea was that it would take a while for the dope to take effect. Music was played to create an atmosphere conducive to these trips. Members allegedly displayed behaviour that ranged from rolling around on the floor, crying out ecstatically to sitting frozen in trance-like positions as the drug took its course. Something tells us this hashish was a little stronger than what you might find on the market today.

Some Hashish Club members (they came and went) weren’t as enamoured with the drug as others. Baudelaire apparently preferred the more social aspects of wine to hashish as his vice of choice. He only tried hashish once or twice and wrote in his book Les paradis artificiels (1869), that he didn’t like the isolating aspects of hashish. Similarly novelist Honoré de Balzac wasn’t convinced of swallowing the dawamesc, petrified that he’d lose mental control (although subsequently, he confessed in a letter that he had in fact tasted the drug under other auspices).

For about five years, the club’s main raison d’être was to indulge in, and explore (for the sake of research of course) psychedelic drug-induced experiences. The players in turn published their personal findings and opinions on the subject. These literary volumes would record every detail of the hallucinogenic events, from the order of decent into the madness, the levels of intoxication to the ridiculous and disturbing imagery of the dead, dying, tortured and tormented. In his recollections, Gautier later published,

“I heard the sounds of colors…A whispered word echoed in me like thunder…I swam in an ocean of sound.” ‘‘goatsuckers, fiddle-faddle beasts, budled goslins, unicorns, griffons, incubi fluttered, hopped, skipped and squeaked through the room.”

Meetings at the club eventually ceased in 1849, after a wealth of information had been published on the intoxicating drug, most notably in Jacques-Joseph Moreau’s 439 page Hashish and Mental Illness. Many members believed that their participation had been detrimental to their ability to write, now seeing hashish as veil impeding a clear view of reality.

Charles Baudelaire

Charles Baudelaire however, became addicted to opium and alcohol, as did his mentor Thomas De Quincey, who died impoverished in Edinburgh in 1785. Baudelaire’s later life also saw decline into semi-paralysis following a stroke. Following his death in Paris in 1867, much of his work was published by his mother, who also paid off his debts. In his seminal work, The Poem of Hashish, Baudelaire concludes of the creative qualities of hashish,

“that hashish gives, or at least increases, genius, yet it cannot be forgotten that it is the nature of hashish to diminish the will; thus it gives with one hand what it takes away with the other; it gives imagination without the ability to use it.”

Source: Cecile Paul – messynessychic.com